The Durbar Squares that are a reflection of our historic urban society are ensembles that were built over more than three centuries by several generations. “This ensemble reflects layers of knowledge that has been accumulated over time as a result of adopting tried and tested approaches,” says Ranjitkar.

The structures in these Durbar Square ensembles date as far back as 16th century. These structures have withstood weathering and degradation caused by natural elements over centuries as well as the effects of natural calamities. There is recorded history of earthquakes in Nepal since 1310 Bikram Sambat or 1255 AD, and ten major earthquakes in the region have been recorded since. Several constructions were made incorporating lessons from disasters that the urban society then witnessed in their lifetimes. The palace complexes in the three durbar squares are interpreted as an example of adapting to this seismic prone nature of the region. The Malla era of 12th to mid-18th century AD that saw the construction of five-story tall temples, constructed royal residential palaces of only two stories of under six and half feet in height with walls of not less than three feet in thickness probably as a measure of resilience to seismic tremors.

“There are several structural elements that were additions in later structures like the decorative horizontal bracing panel that is characteristic of structures only from the latter centuries of the ensemble,” shares Ranjitkar who sees this evolution in structural elements as learning and adapting solutions that were tested through natural weathering and even calamities. “There is so much we still do not know about the science and quality behind traditional methods. There should be research done into the structural elements that gave specific heritage structures resilience – Nyatapola for instance is among our tallest temples and it has withstood the two major earthquakes in our recent history!”

Nyatapola survived the two major earthquakes of 1934 and 2015. This five-tiered marvel is worthy of study so we can understand what elements give it its resilience and strength.– Rohit Ranjitkar, Country Director KVPT

Nyatapola survived the two major earthquakes of 1934 and 2015. This five-tiered marvel is worthy of study so we can understand what elements give it its resilience and strength.– Rohit Ranjitkar, Country Director KVPT

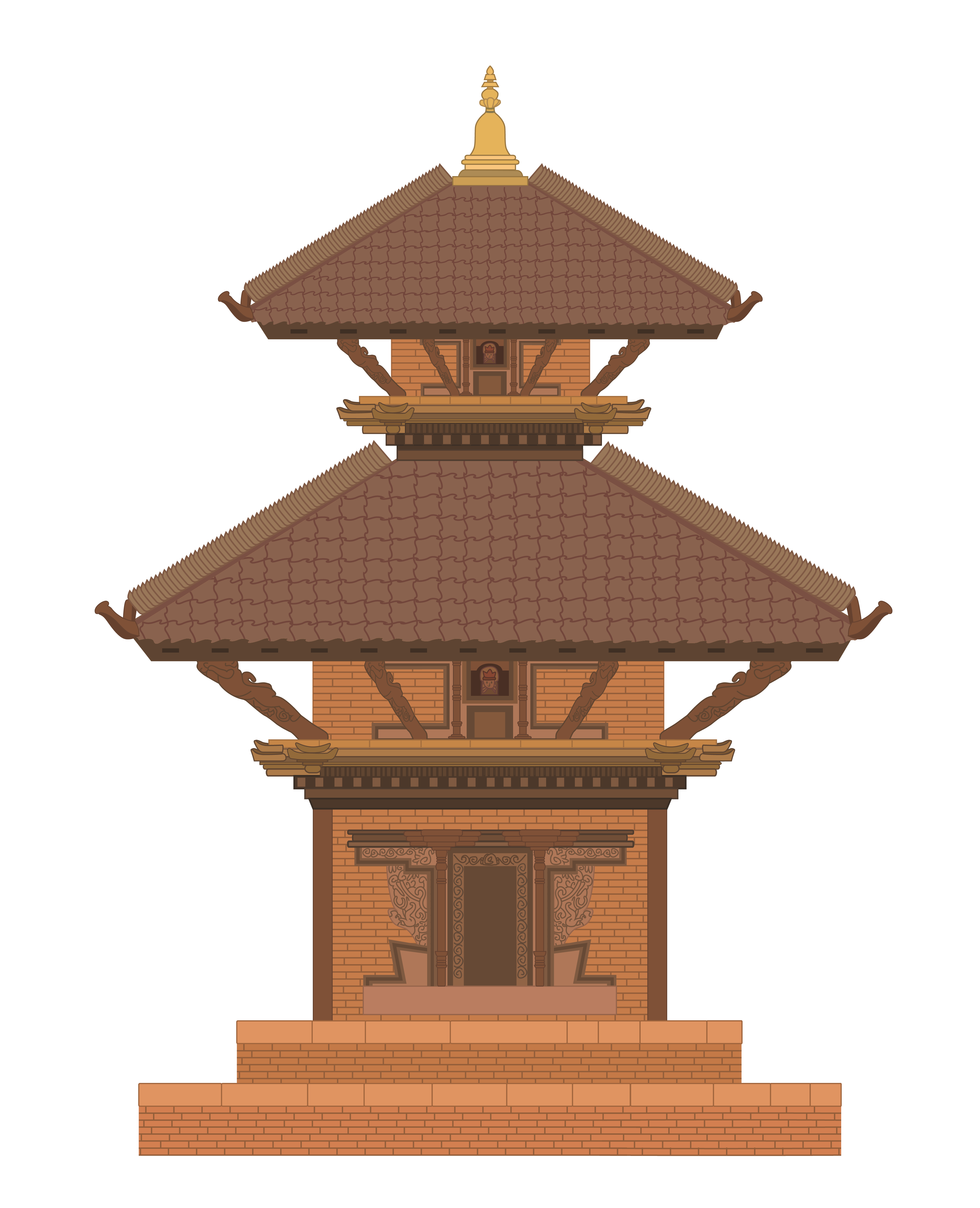

Some of the prominent heritage temples that survived the 2015 earthquake

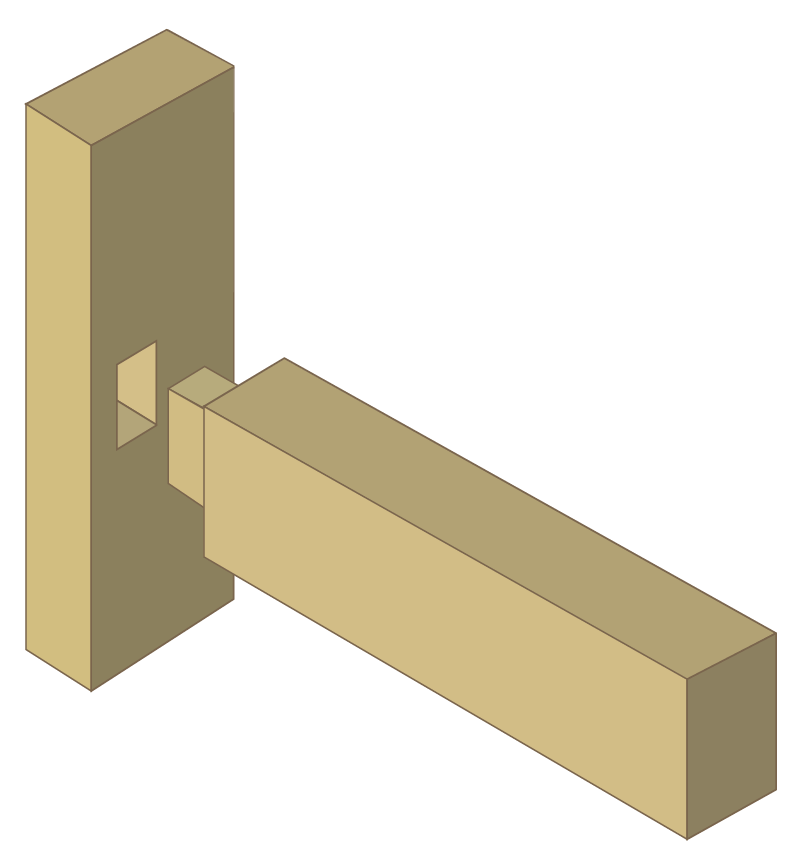

It is intriguing that the fundamentals of heritage structures give a sense of intuitive use of available material and innovative technology to add resilience to seismic action that the region has always been prone to. “The extensive use of wood especially in the skeletal and support system of these structures in the form of pillars and beams, supporting each other on what we know globally as ‘mortise and tenon joints’. All joints and hinges were made of wood with calculative precision giving these structures the advantage of flexibility and ability to sway without falling apart,” explains Kayastha. The principal use of these wooden joints in the structural skeleton and the fact that structures have survived these earthquakes is also a reflection of the precision and accuracy with which these structural woodworks have been crafted as even slight disproportion in these fixtures can cause the wood to split or break.

Resilience was important then, and it is important now. We are still prone to seismic activity and the 2015 earthquake was a reminder that resilience requires priority. The importance of strength and durability in construction is even more pertinent for a geological setting like ours.

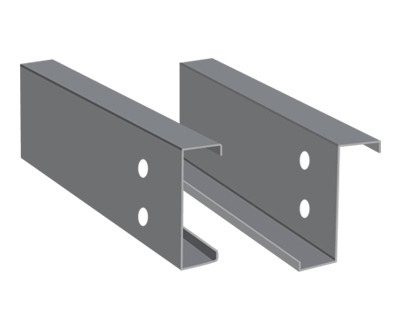

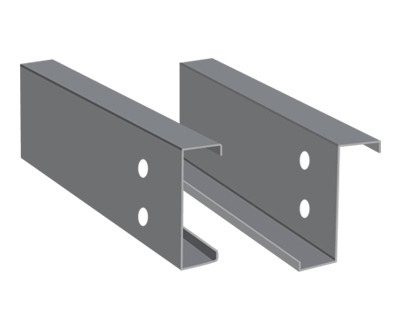

Construction companies have responded to the lessons from the recent earthquake with solutions specific to earthquake resilience. While Panchakanya’s response was introducing Light Gauge Steel which is a preferred material for construction in seismic zones, resilience has been a driver of product development from earlier on. In 2002, Panchakanya made the landmark shift in Nepal’s construction sector by introducing Thermo Mechanically Treated (TMT) Steel. TMT technology was adopted to replace Cold Twisted Rebar steel to produce bars of greater strength and ductility used to construct stronger and safer buildings. “When we introduced TMT, there was a reluctance to use the product due to lack of awareness about the newer technology. The idea was to make available a globally tried and tested product as a better quality solution compared to what was available in the Nepali market,” shares Ujjwal Shrestha, Executive Director at Panchakanya. Today TMT is the standard technology for production of steel bars as well as the standard steel used in constructions across the country.

It is intriguing that the fundamentals of heritage structures give a sense of intuitive use of available material and innovative technology to add resilience to seismic action that the region has always been prone to. “The extensive use of wood especially in the skeletal and support system of these structures in the form of pillars and beams, supporting each other on what we know globally as ‘mortise and tenon joints’. All joints and hinges were made of wood with calculative precision giving these structures the advantage of flexibility and ability to sway without falling apart,” explains Kayastha.

The principal use of these wooden joints in the structural skeleton and the fact that structures have survived these earthquakes is also a reflection of the precision and accuracy with which these structural woodworks have been crafted as even slight disproportion in these fixtures can cause the wood to split or break.

Resilience was important then, and it is important now. We are still prone to seismic activity and the 2015 earthquake was a reminder that resilience requires priority. The importance of strength and durability in construction is even more pertinent for a geological setting like ours.

Construction companies have responded to the lessons from the recent earthquake with solutions specific to earthquake resilience. While Panchakanya’s response was introducing Light Gauge Steel which is a preferred material for construction in seismic zones, resilience has been a driver of product development from earlier on.

In 2002, Panchakanya made the landmark shift in Nepal’s construction sector by introducing Thermo Mechanically Treated (TMT) Steel. TMT technology was adopted to replace Cold Twisted Rebar steel to produce bars of greater strength and ductility used to construct stronger and safer buildings. “When we introduced TMT, there was a reluctance to use the product due to lack of awareness about the newer technology. The idea was to make available a globally tried and tested product as a better quality solution compared to what was available in the Nepali market,” shares Ujjwal Shrestha, Executive Director at Panchakanya. Today TMT is the standard technology for production of steel bars as well as the standard steel used in constructions across the country.